Greek 2018Scottish Opera

Read more about the opera Greek

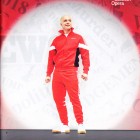

This production of Greek opened in Edinburgh last August, receiving two performances in the wide space of the Festival Theatre. While that allowed lots of tickets to be available, it did give rise to a certain lack of intimacy. The previous stagings were in far smaller venues - Leith Theatre and the Traverse. There were suggestions that the bigger venue was not entirely suitable. This revival for two performances in Glasgow - the first Scottish performances away from the capital - were in the far more intimate Theatre Royal. Musically and dramatically the last of the performances worked well from the off. The revival, crisply directed by Daisy Evans, contained one expected cast change compared with Edinburgh, with Henry Waddngton joining the others. Less expected was the arrival of a new conductor in place of the originally announced Stuart Stratford. Finnegan Downie Dear is rapidly developing a reputation as a fine interpreter of modern scores, and he drew an excellent account of the unusual instrumentation from the Scottish Opera players. The strings alone guarantee an interesting soundworld, with no violins at all, solo viola, two cellos and one bass to offset a wide selection of other instruments.

Susan Bullock, Allison Cook and Henry Waddington all took full advantage of the differentiation of their various roles. Perhaps the singer to gain most from the reduction in playing space was Alex Otterburn, who now had no difficulty projecting both voice and character. The design concept also worked well - the huge panel of Johannes Schütz's set had a door at either side for easy access and quick changes, filled the proscenium and rotated out above the orchestra pit to provide the occasional visual variation. Beginning and ending simply as a white wall, it was used for all sorts of projections that illuminated events, including ketchup from the café doubling effectively as blood.

If there is a reservation, it may be with the work itself. It is, after all, derived from the classical Greek tragedy of Oedipus, and if Greek tragedies have one consistent feature it is surely the sense of inevitable doom confronting the hero, and the tragic catharsis with which the work ends. Operatic interpretations from the twentieth century that achieve this include not just Stravinsky's Oedipus Rex, but, derived from other plays, the Strauss Elektra and Henze's The Bassarids. There are, no doubt, several others. The flippancy that is never far away in Greek undoubtedly disperses the sense of inevitable tragedy - Eddy even delivers a cheery epilogue in which he seems to make light of the whole. However that is clearly a decision taken by the creators when adapting the text, so needn't be an issue in performance thirty years later. This work is an important classic and it was wonderful to see it so well done.

The 2017/18 season of Scottish Opera

The season opened at the Edinburgh International Festival with a new production of Greek, the modern classic by Mark-Antony Turnage, which had its British premiere at the 1988 Festival. There were further performances in Glasgow in January. The main season began with a welcome and overdue revival of Sir David McVicar's powerful production of La traviata. In the New Year there were fresh stagings of another successful recent piece, Flight (Jonathan Dove) as well as Ariadne auf Naxos and Eugene Onegin. As a follow-up to the four operatic rareties mounted as Sunday concerts in 2016/17, the new subjects were rare Russian operas - Tchaikovsky's Iolanta, Prokofiev's Fiery Angeland a Rachmaninov double bill - Aleko and Francesca da Rimini. The fourth of these concerts was a digest of Russian pieces performed by students from the National Opera Studio under the title From Russia With Love. There was also the regular Highlights tour round the Highlands and Islands, this time in two phases, autumn and spring.